Summary

The software industry gross margin structure is often used as the primary indicator for a superior business model in high growth technology investing. However, the focus on gross margin can obfuscate the end goal of building and investing in a company, financial strength to ensure a path of independence and shareholder returns, which are driven by free cash flow margin and free cash flow generation per share. Long-term defensible business models can be built that have lower gross margins, yet near comparable free cash flow margins, when compared to best-in-class software companies. This piece explores the differentiation between ten public non-software companies and ten public well-known best-in-class software companies in three areas (i) margin structure, (ii) the returns each group of companies has produced on a ten-year time horizon, and (iii) how founders and investors should react to scaling a business and investing. I posit that an “n of 1” differentiation should be more of a focus when underwriting opportunities in venture capital investing over a software gross margin structure. Through first principles thinking, this leads to larger business outcome, higher free cash flow margin, and greater shareholder returns for both the founder and investors. N of 1 differentiation can be found in any industry, or sector, and it can be a pure software business, a hardware and software combination, or even no software offering involved.

Introduction

A focus on the software industry gross margin structure as the primary indicator of early potential business success can be shortsighted when investing in the high growth technology space.

Gross margin is a great barometer to assess an organization’s value delivery and its importance throughout any stage of equity investing is not understated. In venture capital and technology investing, gross margin is often treated as the long-term determinant of business outcomes and shareholder returns. On the contrary, for founders, to build a financially independent company and generate strong shareholder returns a consistent focus on free cash flow margin (and free cash flow generation per share) is the proper direction to pursue.

A thin cost of goods sold (superior gross margin) paired with a bloated organization in the operating expense layer is often overlooked. Organizations may fall into this category and promise high free cash flow margins at scale. This is a fair argument depending on the lifecycle of a young high growth company. But what is scale? There are many private and public software companies between $500 Million and $1 Billion+ in revenue with gross margins in the 70%-80% range, yet with single digit or negative free cash flow margins as the unit economics become paralyzed. In parallel, when growth decelerates, either in a difficult macroeconomic environment or due to other specific business challenges, the revenue growth no longer justifies the costs and an imbalance occurs between topline growth and bottom line results (the appropriate revenue growth versus absolute revenue is a sliding scale dependent on multiple factors not discussed in this piece).

There is a balance of cash burn and investing in a business to achieve high revenue growth, but the goal is to ultimately generate as many cents as possible for every dollar brought in. High gross margins and low free cash flow margins could be a sign that the product is not strong enough to sell (and expand at customers) at scale, leading to a high-level of S&M expense. At an R&D expense layer, it may indicate that product investment only yields slight improvements to match competition in a commoditized landscape. These operating expense layers allude to deeper signals of a competitive environment with lower levels of differentiation between offerings.

The best companies in the world flourish with both high gross margins and high free cash flow margins, and many are enterprise software companies. Founders, however, should not painstakingly focus on gross margin if their company’s business model is inferior to best-in-class software organizations on this metric. The proper alternative for founders is to aim at the n of 1 mindset as a true driver of differentiation. Overtime, moat establishment is the true determinant to compound cash flow per share and generate sustained shareholder returns.

N of 1 does not mean to exclusively target moonshot ideas with binary risk. The heart of the concept is to find a unique and difficult problem and address that problem with an offering that alleviates pain for the end customer so the product has increased pricing power in future periods.

The market forces that anchor a traditional software model with a gross margin emphasis as the sole way to build a great business with large outcomes should not occur. At the same time, praise is given to the fantastic software businesses built in both the public and private markets where the gross margin emphasis is necessary.

In this piece, I seek to offer a comparison between non-software companies with lower gross margins but with strong free cash flow margins and strong shareholder returns, to well-known best-in-class software companies. The goal of the analysis is to illuminate misconceptions and offer a renewed mindset to build exceptional businesses in any industry, or sector, with a business model that is pure software, a hardware and software combination, or even no software offering involved.

How We Got Here with Gross Margin Emphasis in the Technology Industry

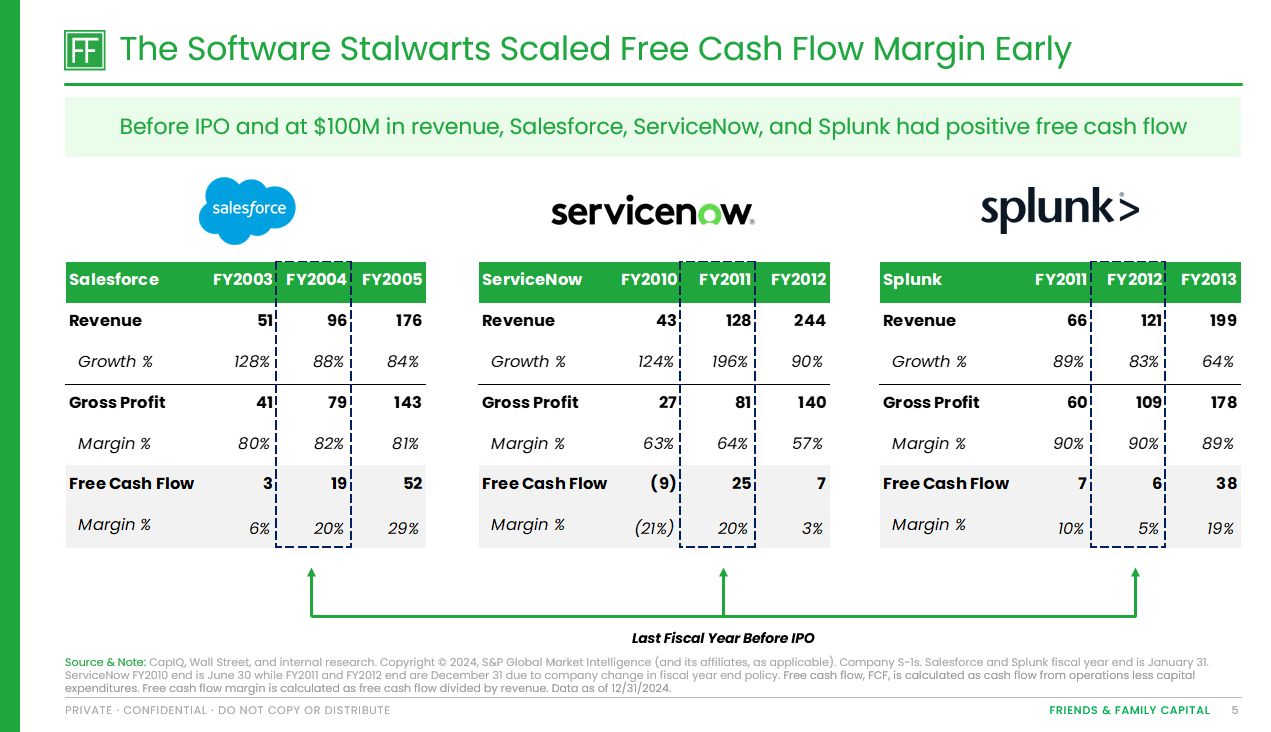

When hypothesizing the best business models, the recurring revenue nature of high gross margin software companies goes to the top of the list, and rightfully so. Companies such as Salesforce, ServiceNow, and Splunk (acquired by Cisco in March 2024 for $28 Billion) display that the lower cost of product delivery can provide leverage to operations and create a unique level of sustainable non-cyclical free cash flow.

Companies like Salesforce, ServiceNow, and Splunk hooked the venture space on high gross margins. Highlighted in the blue outline below is the final fiscal year before each respective company had their IPO. The gross margins for the three companies were paired not only with positive free cash flow margins but also ~2x revenue growth on a year over year basis. These exemplary fundamentals are still best-in-class and hard to accomplish even in the current era of venture investing at a similar revenue scale. In many ways, investors remembered top gross margins, yet forgot the overall context of these financial profiles.

Gross margin became popular in the venture capital mindset and the software space because once you build the software product, the incremental delivery should be minimal. The software model is fantastic because of this important concept. Cloud hosting costs now make up the majority of cost of goods sold for software companies. The major downside is that because of the potential to build a great software business with a large margin opportunity, competition increases and more costs are necessary to sustain that competitive advantage to distribute, build, and maintain the product. Such an environment can lead to many commodity and few n of 1 offerings.

Contrary to the software stalwarts are software companies with high gross margins but are unable to translate to healthy free cash flow margins even at $500 Million to $1 Billion+ in revenue. These businesses are applauded for the great products and innovation they have built, nevertheless investors should question the operating components of these businesses between gross margin and free cash flow margin. Eventually, if course correction doesn’t happen, such companies will dilute founders more and erode shareholder returns.

Additionally, gross margin can run into a cost allocation problem. Some companies may classify costs to skew more towards operating expenses rather than cost of goods sold. For companies where this may occur, an inflated gross margin might suggest potentially great free cash flow margins at scale. However, due to the cost allocation facade, those potential free cash flow margins may not come to fruition because the hidden operating costs were always there, just allocated to the wrong line items.

But what about the companies that have a high burn rate (negative free cash flow) but continue to scale fast? Many of the top software companies in the public and private markets fall into this category. If a large product differentiation drives unique revenue growth but negative free cash flow, the pursuit of that growth should still continue. This concept is not to replace the end goal of free cash flow margin stability. Snowflake is a great example of a company that scaled in this manner.

Snowflake’s path displays a high burn rate but alongside exceptional growth. Even with macroeconomic tailwinds during the years outlined, Snowflake maintained some of the best growth ever at its respective revenue scale and did accomplish a ~40% point free cash flow margin lift in two years between FY 2021 and FY 2023.

A Renewed Mindset for Building a Large Business in the Technology Industry

When investors see early stage companies with a lower gross margin structure, they often look the other way as they reminisce about the stalwart software firms. Investors who think in this manner have bypassed some of the most successful companies in the public markets today.

As a topical example, an area where there is much focus now in the venture space is hardware companies. In certain industries, the physical world has gone many decades without an update to the mission critical hardware necessary to thrive. When assessing a company that builds a unique hardware offering, there is inherently going to be more costs involved to deliver the product, leading to lower gross margins. However, with n of 1 hardware companies, the potential to capture a large market and sustainable long-term free cash flow margins (even with capital expenditure considerations) is available for the patient investor. When creating a unique offering that is more difficult for competition to usurp, pricing power increases and a leaner more disciplined organization with less operating expenses can be achieved in a steady state scenario.

To show the proof of success that can be found in lower gross margin structures, I have selected ten organizations across different sectors in which software is not their primary focus. There is always bias into selections and these companies are meant to demonstrate what businesses look like that have gross margins lower than best-in-class software companies, but near or higher free cash flow margins than best-in-class software companies. These ten organizations represent some of the largest enterprise values in the world. Their cost to deliver the product is higher than the software space but the value they deliver to their end customers, whether businesses or consumers, is exceptional. All companies discussed are public companies as their data is available to anyone.

The companies represented span networking, industrials, restaurants, aerospace, veterinary, manufacturing, and communications. Since the beginning of 2015, as an equally weighted basket, these companies produced investment returns of a 9.5x multiple on invested capital and a 25% IRR. For comparative measure, over the same time period the S&P 500 and Nasdaq Index’s returns were 2.9x and 11% IRR, and 4.1x and 15% IRR, respectively. At the margin view, median gross margin for this set of companies is 55% with a median free cash flow margin of 21%.

At times, hardware companies are falsely framed to be business models that are inferior to the software business model. However, when analyzing companies like Arista, Heico, and Motorola Solutions, the narrative falls apart. Here are businesses with a heavy hardware component that continue to produce great returns for their shareholders. Gross margins at these businesses are lower than best-in-class software organizations but free cash flow margins and capital allocation are strong. These companies own their market and the product is proven.

What can be learned from these companies? Each one of them has a unique offering and can be defined as n of 1. IDEXX is the vendor of choice in the veterinary space for the specialized equipment they produce. Caterpillar is synonymous with quality and durability in the heavy machinery sector. And TransDigm is a model firm for other aspiring conglomerates on how to manage results, seek value, and execute M&A over decades.

Best-in-Class Software Produces Some of The Strongest Businesses

Although the initial part of this piece was to present non-core software businesses it would be remiss, especially as a venture investor, to not highlight why software platforms are so well received as investment opportunities in the private and public markets. The firms below have built and improved upon exceptional products for decades. They are market leaders and earned both high gross margins and high free cash flow margins. These organizations demonstrate why high growth venture investing is so strongly correlated with software investments. Again, all companies discussed are public companies as their data is available to anyone.

As displayed, superior software platforms can accomplish both high gross margins and high free cash flow margins, and deliver exceptional returns to investors. Since the beginning of 2015, as an equally weighted basket, these companies produced investment returns of a 7.4x multiple on invested capital and a 22% IRR. Again, for comparative measure, over the same time period the S&P 500 and Nasdaq Index’s returns were 2.9x and 11% IRR, and 4.1x and 15% IRR, respectively.

The past ten years of returns for this set of well-known software companies is slightly lower than the returns of the non-software group. Nevertheless, ten separate companies in each category could have easily reversed the results. Choosing companies in different stages of their lifecycle and maturity, and over different time horizons of return measurement will also change the outcomes. Private versus public market companies chosen will likewise impact the results.

At the margin view, median gross margin for the set of software companies is 78% with a median free cash flow margin of 27%. As a reminder, the non-software companies had a median gross margin of 55% with a median free cash flow margin of 21%. Interestingly, the difference between gross margin for the two sets of companies is nearly 4x that of the difference between free cash flow margin.

A final consideration between the two criteria of companies represented is stock-based compensation (SBC) expense. The debate over the treatment of SBC in the investment world is broad and never ending. In this analysis, I provide a simple framework to consider.

It is more common for software and venture backed companies to compensate employees with stock-based rewards than non-software companies. SBC expense is a non-cash expense, and so does not negatively impact free cash flow. If these same software firms measured earlier compensated employees with more cash and less equity rewards would the free cash flow margin at the median be the same between the sets of companies?

The answer in this case is the free cash flow margin is higher for the non-software companies at the median if all SBC expense is treated as cash compensation for both sets of companies. With the aforementioned adjustment, the non-software companies now have a median free cash flow margin of 19% and the software companies have a median free cash flow margin of 15%.

What Does This Mean for Founders?

The ultimate point for founders is that you can build the company you feel is most impactful while still achieving a huge outcome. The over-emphasis on a pure software only model with gross margin as the focus can thwart some of the best ideas and founders.

For founders, don’t solely focus on the cost of delivery for the product, rather understand the total cost to run the business efficiently. It is a backward representation when business metrics are displayed that act as if operating expenses don’t exist, especially when such operating expenses are driving cash flow negative. For founders, this path will eventually dilute your own stake at a greater rate. The notion that you don’t need the rest of the company to support ongoing operations is the incorrect mentality when building a business to scale and inhibits both financial independence for the company and long-term shareholder value creation.

The most challenging problems that no one else wants to tackle can often lead to the largest outcomes. Scaling the nth company that does a similar task with new tooling can often be a pathway to an already competitive environment with low differentiation. Software is always being replaced and incumbents do get usurped, but strive for strategic advantages to create long-term defensibility instead of what makes the best gross margin story – no matter what industry you are building a solution for.

One of my favorite quotes from the legendary investor John Templeton underscores the conversation, “It is impossible to produce superior performance unless you do something different from the majority.”

Conclusion

To provide a metaphor to running, I think about gross margin as the speed workouts to build the base of fitness to target a goal time in a race, and free cash flow margin as race day performance. You can build incredible fitness in your speed workouts but if you don’t deliver results on race day the speed workouts are frankly irrelevant. Race day is where the money is made and where your personal bests are memorialized. In marathoning, it is always common to hear of runners who couldn’t hold it together the last 25% of the race to hit a desired time. I have had such an experience myself. When this happens, runners will caveat they were on pace through 20 miles to hit their goal, and emphasize their fitness, and that they could have hit the time if it wasn’t for the wave of fatigue and the lactic wall that came upon them after 20 miles, as if that is the distance of a marathon (to the non-runner a marathon is 26.2 miles). To bring it full circle, those first 20 miles for these runners are the gross margin, irrelevant if you can’t capitalize on the end goal, free cash flow margin, the full marathon distance.

Margin structure determines how a founder can achieve financial strength to ensure a path of independence while providing shareholder returns. A company’s margin structure ultimately erodes or raises shareholder value. To underwrite investments in the high growth technology space it is important to understand the true levers of the business, only then can the potential free cash flow composition be parameterized. There is an incredible opportunity right now to back founders that are redefining industries with a hardware first or non-software solution, combining hardware with a unique software platform, or having a best-in-class enterprise software offering that provides unique and differentiated customer value. To strive for any n of 1 solution is recommended.

I seek to back these founders who take risks where others are apprehensive to look. It is at that point of discovery where the seeds of success are sown and value creation is highest.

The information presented herein is my opinion and does not reflect the view of any other person or entity. It is for informational purposes only and should not be construed as an investment recommendation. Data as of December 31, 2024. Data sources include CapIQ, company filings, and internal research. Copyright © 2024, S&P Global Market Intelligence (and its affiliates, as applicable).